Dear Members,

In medical school we are taught to maintain a “safe” psychological distance from our patients, and not get “too close” because caring too much may cause us to lose our scientific objectivity, and/or cause us to suffer too much in the event that our patient ends up having a bad outcome.

While there are aspects to this view which seem logical, I have come to see this as a terrible lie which is paradoxically responsible for much of the suffering of contemporary healthcare workers, never mind the recipients of our care. It is precisely by fostering and encouraging a deep human connection with our patients that a healing bond is established, which I believe our patients need and deserve. But it is not just patients who need deep and meaningful connection, as only through such relationships do we, the physicians and healthcare providers, find meaning in the long hours of our demanding work.

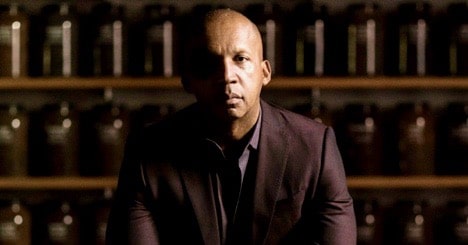

A similar warning of “maintaining safe distance” with clients is given to law students—to avoid becoming too invested in the outcome of defendants who may end up with harsh sentences in court in spite their lawyer’s best efforts. This contrasts with the approach taken by Bryan Stevenson, the defense attorney from Alabama who has devoted his life to exonerating innocent death row prisoners and confronting abuse of the incarcerated and the mentally ill. He explains that, “You can’t understand the most important things in life from a distance. You need to get close.” Stephenson famously developed strong connections to those he defended, and came to love them and care for them as though they were his own family.

Perverse incentives, conflicts of interest, and hidden agendas abound in the practice of medicine. The antidote for this is human connection rather than the frequently transactional (and at times extractive) relationships of the medical industrial complex.

The way back and the way forward that we seek is in the opposite direction of the anachronistic med school and law school dictums to avoid close relationships with those we serve. The path we seek is one of reclaiming the dignity, the decency, the heart-break-opening beauty of caring for another human being from the depths of our soul. Saying yes to the pain of bearing witness in deep empathy and solidarity to another person’s suffering, precisely when we have exhausted all of the tools, techniques, and tricks of our trade, and when (after consulting colleagues who are experts and specialists in other areas of medicine) we have little more to offer than our presence—that too is the work of a healer.

As much sadness as this wells up in our hearts, it is a kind of sadness which is transmuted into unity, into connection, and into love. This is ultimately the greatest, most potent, most universal healer of all. And with infinite paradox, it heals us too. This connection heals the broken hearts of the wounded healers (which we all are). Indeed, it is the only thing that can.

It is telling that both the word “healing” and “love” are all but absent from mainstream healthcare. In fact, they are generally considered taboo and gauche by the medical establishment. The vanity and pretentious artifice of withholding our hearts and our caring in order to create a “safe distance” at an arm’s length in order to ostensibly build a protective barrier and buffer against our own ability to grieve along with our patients when illness progresses beyond our capacities of calling life back—this lies at the root of the sickness of our healthcare system. What is missing is not our emotionality, but our emotional intelligence.

There is nothing too complex, esoteric, or mystical about this recalibration. It is simply the path of finding one’s truest, deepest, most meaningful purpose and calling, one’s life work, and realizing with a dawning ironic smile that this grand mission of ours was never about “us” in the first place. Rather, it is about our offering and our contribution to others, to those we serve, to our patients, to the world, to our children, to those who come after us.

To whom else or to what other cause ought we dedicate our professional lives?

In this devotion and dedication, and by way of the reverent and humble offering of our “gift,” we get our personal and professional integrity back. Through this act of giving we reclaim our souls and rediscover our life-force, our competence, our unique gifts, our joy. While these attributes are not entirely missing from our profession, they are being threatened every day. It’s shocking to learn that we medical doctors now top the list of professions with the highest rates of suicide. And every day, somewhere in the US, one of our physician colleagues takes his or her own life.1 Many of the thoughtful and caring human beings entering our field have become disillusioned, disheartened, dejected, depressed, and jaded, and wonder how they ended up investing so much of their lives in a career so hollowed out by the various self-serving promoters of false aims and false claims.

I believe that we primary care physicians must face our many challenges together—in a unified way—and release ourselves from our complicity in a system and paradigm which, although miraculous at times, is all too often inhumane, insane, and unethical. Our current “old school” medical system, which causes the “10 Heartbreaks,” now requires the implementation of our collective wisdom in order for its redesign to be life-affirming and supportive of human flourishing.

By recommitting to our sacred vows and pledging our devotion to the well-being of our patients most of all, but also to that of our communities, our families, our children, (as well as our own), the illusion of separateness and distance from one another can be dispelled.

True meaningful healthcare reform will not blossom from a hyper-centralized medical industrial oligopoly which only knows how to commodify synthetic drugs and surgery. It will arise from local networks which are able to connect the dots between healthcare workers and farmers, artists and leaders, entrepreneurs and teachers, and which recognize that community health and resilience are interdependent, just as individual and community health are interdependent.

Designing and building such networks (which we define as “salutogenic eudaimonic” networks) requires both a bird’s eye view as well as an insider’s angle to the systemic aspects of healthcare, as well as a deeper understanding of what it actually means to be healthy and to heal. Those of us who know what it is like to sit with a dying patient and their family as they take their final breath, or to look another human being in the eye and explain that their results indicate a serious diagnosis, or to hold someone’s hand and reassure them that treatments and therapies exists to ameliorate their condition are now called to step forward and speak.

We must speak clearly and precisely. We must discern the things we do that really matter from the mere distractions, the fundamental from the trivial, the essential from the marginal. In modern medical practice, these crucial distinctions often get conflated, manipulated, and obfuscated by forces which do not have the best interests of our patients and our communities in mind.

We can no longer afford to let this happen.

Just because many have lost faith in Washington does not mean that our nation lacks real leaders and exemplars of wisdom and virtue. Let us stand up for and stand behind the true leaders amongst us. I recommend watching Just Mercy, the recent biographical film about Bryan Stevenson’s life and work, starring Michael B. Jordan, as well as learning about his work at the Equal Justice Initiative. Stevenson has much to teach us about closeness, connection, caring, and community leadership.

Reference links: 1. https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/news/20180508/doctors-suicide-rate-highest-of-any-profession# 1